We began by talking about cyclical narratives so we must begin again now in the final chapter with a cyclical narrative that was prescribed a couple of millennia ago. Religious empires spread it all over the world in linear script, where it remains far too easily ignored… far too easily ignored because it seems to also convey preventive therapies that might have avoided current crises of Anthropocene and climate change. It could not be ignored in the foregoing cyclical history, because it is also one of the names given to the musically expressed aspirations of enslaved Africans in the Americas.

The word is jubilee. It is often understood nowadays as a 25th or 50th anniversary, or as a big celebration. In the musical expressions of enslaved Africans, however, it connoted emancipation. The Biblical source material that the enslaved drew upon to create spirituals (also known as jubilee songs) described 50-year cycles in which the ecology of the land was renewed by allowing it to rest, the ecology of the economy was renewed by forgiving all debts, and the ecology of human community was renewed by freeing all of the enslaved. People who had lost their homes and lands were to be returned to these at the beginning of each jubilee cycle as well. The latter was justified and compelled by stating that land could not be permanently owned, but could only be held temporarily by people, because all of the land actually belonged to God.

This seems to offer one example of how what I have called a compassionate community or human community ecology actually worked… or might have worked if it had been actually practiced. Although it was prescribed in linear prose as “law” that was subsequently spread globally by expanding religious empires, it was never put into action. My argument here is that it is impossible for linear prose to convey cyclical truths, which must actually be experienced in the cyclical movements and ecologies of cosmic time. The only way for the empires to convey this truth would have been to actually do it.

There was one aspect of this law that the empires did practice and propagate though. That was the stipulation that people and lands that did not belong to this particular tribe could be abused at will and in perpetuity by member of the tribe, because such stipulations of compassion did not apply outside of actual tribal members or actual tribal property. In other words, non-tribal members were relegated as less than human. This is also how the Roman empire treated non-citizens. It is also the arrogance that initially enslaved and later oppressed Africans and their descendants in the Americas.

The point for this narrative is that such arrogant systems only really “work” in linear narratives. In the real-world cyclical time of ecology and the cosmos–in which everyone is really interconnected (particularly in the case of global empires)–each generation of such a system effectively pollutes and sabotages its own succeeding generation. Linear narratives focus on winning and losing battles and on exceptional individuals. Cyclical narratives, however, can show the long-term effects of pollution and sabotage from generation to generation.

I chose to label this concluding chapter as “mono-compassion-ism” because this is obviously not a theological perspective. It’s not about who’s in charge. It’s more of a we-ology of human community ecology. It seems to be a fundamental characteristic of arrogance to worry and argue about who’s in charge and how to please them. Looking at history from a cyclical perspective, however, suggests that who’s in charge, at least in terms of empire, is never who we might be told or think it is.

For instance, Buckminster Fuller, the 20th century creator of “geodesic domes” and self-styled technological revolutionary, pointed out in his 1980 monograph Critical Path that the original flag of the American Republic was only slightly modified from that of the British empire that it broke away from, which itself was only slightly modified from that of the East India Company that profited handsomely from both sides of the conflict (Fuller 1980).

The point here, is not to call names. To me, mono-compassion-ism does not exclude monotheism, but focuses more on action than on concepts–more on living in harmony with creation than on arguing about the Creator. It poses a perhaps unachievable goal of absolute compassion individually and collectively, while realizing that in real life humans end up making compromises. So a previous version of this closing chapter title was named to paraphrase the subtitle of Martin Luther King’s posthumous publication Where Do We Go from Here: as Arrogant Chaos or Compassionate Community? The question still seems operative today, even more so perhaps.

Various “religions” in such a context become different cultural approaches to cultivating a religious or perhaps compassionate consciousness of life experience in whatever ecological context becomes appropriate for that culture. To paraphrase the urban bard, it ain’t nuthin’ but compassion anyway. In a globalizing world then, different cultural approaches to cultivating compassionate community become less a matter of different organizations to belong to and compete over than complementary schools to potentially learn from.

From what I’ve written so far, things may not look good in terms of the global struggle of compassion vs. arrogance, but I’m putting my faith in the compassion that has managed to arise in every generation past, as if that’s what we’re really made of. Might the rising of the oceans finally move humankind to become aware of, share, and alleviate the suffering of fellow people and communities throughout the globe?

In the foregoing cyclical narrative, dance, drum, and song (which is where the “music” comes from) makes such connections orally, aurally, kinesthetically, and emotionally. It is not limited within any particular denomination or dogma or even necessarily within any religion at all. It manifests the common-sense compassion of the river as elder, which must take priority over the ever-present temptation to arrogance that comes with cutting bigger and better paths.

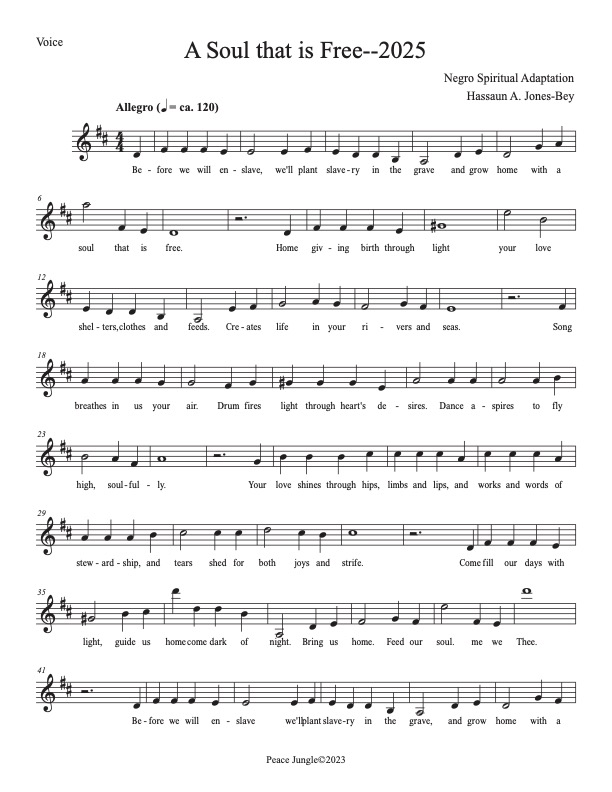

I’ve attempted to represent that in what follows:

Introduction / Chapter 1 / Chapter 2 / Chapter 3 / Chapter 4 / Chapter 5 / Chapter 6 / Chapter 7