Direct continuations of African religion as happened in Brazil were rare in the colonies that would eventually become the United States of America, due to Protestant as opposed to Catholic religion, a lower population density of enslaved Africans than in the Caribbean and South America, and prohibition of ethnic meetings. Even without drums and perhaps even without specific memory of ethnic African traditions, however, compassionate Blackamerican communities were born anyway in fertile agricultural ecologies like the river deltas of the Georgia Sea Islands (Raboteau 2004: 210-9).

Enslaved Africans were often prohibited from any religious expression at all and received torturous punishments, sometimes to death, if they were even caught praying (Raboteau 2004: 210-9). Many were also prohibited from learning to read, and those who were allowed to practice modern Western religion were usually taught it in a way that would make them into more docile disposable commodities (Kendi 2019: 22).

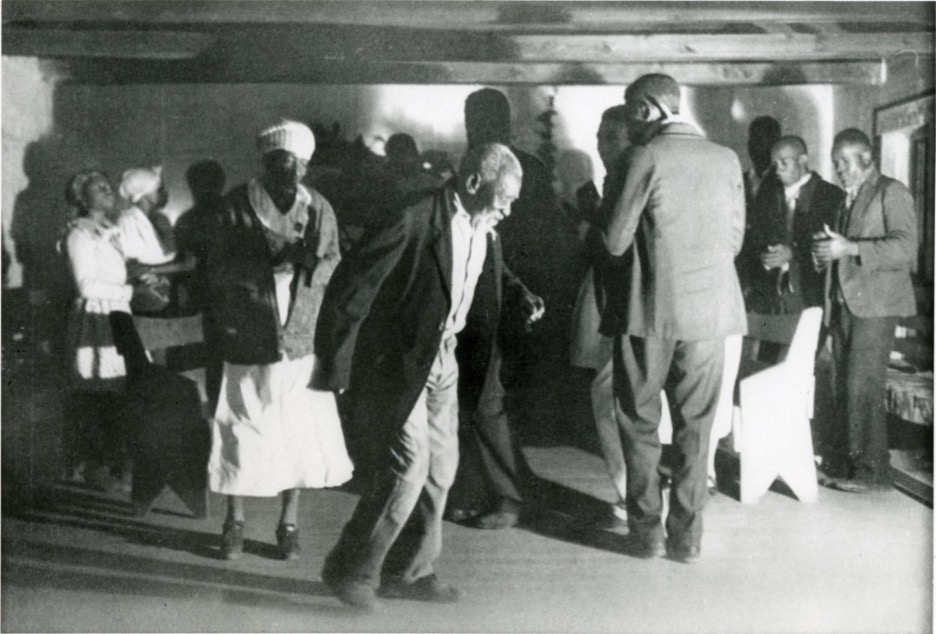

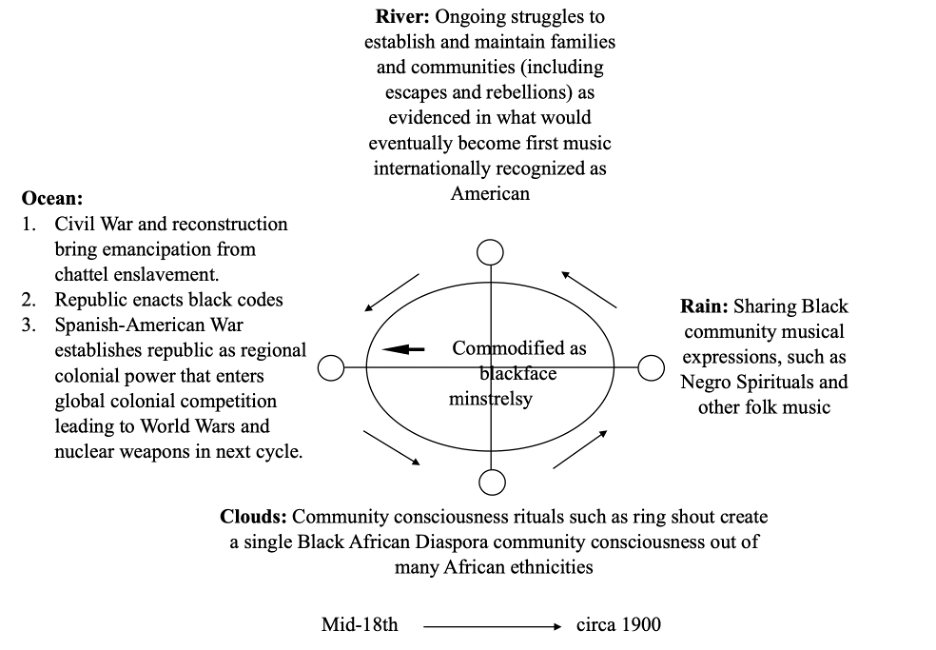

So enslaved Africans connected their actual religious experience with the modern Western religions of their new environment through “spirituals” and other songs that continued African oral tradition of documenting their actual experiences. The songs were often transmitted and shared through communal rhythmic dance (Fisher 1998: Locations 110-251) referred to as a ring shout in the Americas when danced for religious purposes.

In the 1930s, research published by Lorenzo Dow Turner (1890-1972) seemed to connect this Blackamerican ritual (as observed among descendants of enslaved Africans in the river deltas and marshlands of the Georgia Sea Islands) to similar rituals and linguistic features in Bahia–as shown in the illustrations and text below from a 21st century exhibit of Turner’s work at the Smithsonian Institution.

Turner’s pioneering work, which in the 1930s established that people of African heritage, despite slavery, had retained and passed on their cultural identity through words, music and story wherever they landed. His research focused on the Gullah/Geechee community in South Carolina and Georgia, whose speech was dismissed as “baby talk” and “bad English.” He confirmed, however, that quite to the contrary the Gullah spoke a Creole language and that they still possessed parts of the language and culture of their captive ancestors. Turner’s linguistic explorations into the African diaspora led him to Bahia, Brazil, where he further validated his discovery of African continuities….

Stuckey described the religious purposes of the ring shout and related oral traditions carried over from African burial ceremonies as providing “bridges to the hereafter.” This was combined with the Western Christian narrative in the Blackamerican burial ceremony without any conflict. Stuckey wrote,

The two visions of religion in the tale, the traditional African and the Christian, were complementary and explainable in relation to the African view of religious experience, which does not function from a single set of principles but deals with life at different levels of being. The … center of the African’s morality is the life process and the sacredness of those who brought him into existence. … The maintenance of this continuity from generation to generation is justification for his being and the basis on which he determines proper behavior.

Such rhythmic song and dance–expressed in the European language and religious tradition of America–gave birth to a Blackamerican people: speaking American language, needing to work out life in American culture, and sharing a common oppression beneath a “white” American religion that denied their “black” religious experience. The songs that drew themes and lyrics from “white” American religion came to be known as “Negro spirituals.” Fisher describes their evolution over time in response to changing situations from the formation of the republic up through the emancipation (Fisher 1998).

| “Sinner Please“ | 1740-1815 | Camp meetings start replacing African secret meetings |

| “Deep River“ | 1816-1831 | Hope of returning to Africa |

| “Steal Away“ | 1800-1831 | Focus on revolt |

| “You’d Better Min’“ “I am Bound for the Promised Land” “When I Die” | 1832-1867 | Suffering under white backlash to Nat Turner’s rebellion: Evangelization, escape, conciliation, hope of returning to Africa. |

| “Oh Freedom“ | 1861-1867 | Emancipation |

W.E.B. Du Bois wrote that in relationship to their percentage of the population, more enslaved Africans and their descendants fought to save the union during the American Civil War than did Americans of European descent. He also wrote that it was the Blackamerican effort that made the difference between winning and losing (Du Bois 1999).

Blackamerican folk music and expressions, once shared with new immigrants as a way of community building at the bottom of the American economic and social ladder, became blackface minstrel shows. Such entertainment demeaned and degraded Blackamericans, while the other new immigrants learned how to become white enough to move up the social and economic ladder (Bowser 2012: Kindle locations 1564-86).

After the emancipation, chattel enslavement was no longer legal. So, “white” America enacted “black codes” to maintain the white colonial arrogance by keeping Blackamericans as its disposable commodities at the bottom of the social and economic ladders. Blackface minstrelsy gave birth to what would eventually become a global entertainment industry. The emerging American empire also started to acquire colonial possessions overseas as the British had done previously (Immerwahr 2019).

Introduction / Chapter 1 / Chapter 2 / Chapter 3 / Chapter 4 / Chapter 5 / Chapter 6 / Chapter 7