C. Eric Lincoln defined the “black religion” he wrote about half-a-century ago in terms of religious experience. Enslaved Africans and their descendants in the Americas have struggled for centuries with a profoundly religious “double consciousness” of both the “black” disposable commodities that “white” America attempted to make of them and the images of God they actually were. Lincoln wrote:

In short, black religion is a conscious effort on the part of black people to find spiritual and ethical value in their understanding of history. Their history. This is neither parochialism nor racism. Rather it is the realization that even as God is above history [God] acts in history, and that somewhere in the flux, at some time the individual is confronted with the question of what the acts of God mean…. Out of his [or her] understanding of God, in the context of [her or] his own experience, [a person] gropes for meaning and relevance. Assurance and reconciliation. This is religion. When the context of that groping is conditioned by the peculiar, anomalous context of the black experience in America, it is black religion (Lincoln 1974: 1-3).

In articulating this emergence of religion out of experience, Lincoln referred to “black” people at least once and perhaps more often as “Blackamericans” (Jackson 2005: Kindle location 235). I will continue that practice in what follows because the people who enslaved Africans, brought them to the Americas, and called them “black” did not create “black people.” The enslavers purposefully and arrogantly destroyed the ethnic identities and dignity of African people.

The creation of Blackamerican people came through generation after generation of enslaved Africans and their descendants continuing to feel and express compassion for themselves and for one another. The 500-year evolution of Blackamerican musical expression, both sacred and secular, seems to provide a historical narrative of such Blackamerican religious experience, regardless of whatever particular religion the people actually practiced. Such a narrative also turns out to be very well documented because of the extensive manner in which the larger society commodified everything about these people, along with their physical bodies.

The Black Church evolved, not as a formal, black “denomination,” with a structured doctrine, but as an attitude, a movement. It represents the desire of Blacks to be self conscious about the meaning of their blackness and to search for spiritual fulfillment in terms of their own understanding of their history. There is no single doctrine, no official dogma except the presupposition that a relevant religion begins with the people who espouse it. Black religion then cuts across denominational, cult, and sect lines to do for black people what other religions have not done: to assume the black [person’s] humanity, … relevance, … responsibility, … participation, and … right to see [her- or] himself as the image of God (Lincoln 1974: 3).

While there is no single doctrine or official dogma, as Lincoln points out, I suggest that there is a single word for what it is that “cuts across denominational, cult, and sect lines to do for black people what … religions have not done.” That word is “compassion” in its root sense of sharing (and in so doing, also alleviating) suffering. I understand what Lincoln calls “Black Religion,” then as no more and no less than the compassion that happens to be the fundamental essence or purpose of religion itself.

To free Lincoln’s Black Religion from enslavement in linear prose, I begin by associating compassion with the cooling and soothing movement of water, which is something that religious and cultural traditions throughout the world seem to do. The English language translation of an Akan proverb below is about the intersection between a river and a path.

The river crosses the path,

the path crosses the river,

who is elder?

The path was cut to meet the river,

the river is of old,

the river comes from

“Odomankoma” the Creator.

I imagine this proverb as describing a “we-ology” of compassion (or a “human community ecology”) instead of a theology of religion. It doesn’t preclude any theology but doesn’t require one either. In this context the river might be described as “elder” because it provides an example of healthy community ecology.

River water falls to the earth as rain. Rainwater gathers into freshwater rivers that flow into saltwater seas. Solar radiation distills fresh water vapor from the seas. The vapor accumulates in clouds to start the cycle over again.

Similarly, humans are born as helpless individuals who must depend upon and learn how to support one another through rivers of family and community up to and throughout adulthood. Like fresh river water emptying into saltwater oceans, individuals in communities eventually die and return to the earthly biosphere, but compassion amongst humans in families and communities brings life from the biosphere back into human form, to repeat the cycle generation after generation.

Unlike a river, however, a path is cut by human hands. It plays an essential role in community life because it provides access to the life cycle of the river, to other human communities and even amongst people in the same human community. It facilitates all sorts of exchanges, including the exchange of useful and often essential commodities. The path, however, does not have an environmental life cycle. Quite the contrary.

Paths—which have become roads, streets, and freeways in the modern world—are created by people who must kill and otherwise deter plant, animal, and even human life that might otherwise grow and live there. Equating the path with the river—or even more so exalting the path above the river—would seem to miss this point. It would seem to imagine a human capacity to kill as equal to or even greater than ecological “compassion” that births, stewards, and recycles life.

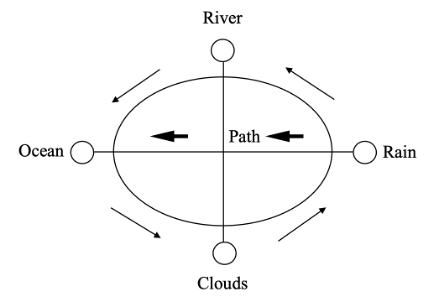

Equating the path with the river–or even worse exalting the path above the river–then becomes like the opposite of compassion: an arrogance that if not recognized and consciously corrected becomes ruthlessly self-destructive, because it literally exalts death above life. My conceptualization of the river-and-path proverb is illustrated in the image below.

In this diagram the river is represented by the vertical axis and the path by the horizontal axis. The intersection of the axes might be thought of as representing what can be shared in words. The ellipse represents the actual water cycle that describes the true identity, home, and purpose of the river.

Introduction / Chapter 1 / Chapter 2 / Chapter 3 / Chapter 4 / Chapter 5 / Chapter 6 / Chapter 7